The year was 1983. I was a young Second Lieutenant, and our Regiment -75 Medium Regiment (Basantar River) – was deployed at the Pokhran Field Firing Ranges in Rajasthan. The same arid expanse that witnessed India’s nuclear dawn. We were there for our annual gunnery exercises, firing the medium guns that were our lifeblood.

After the firing concluded, our Commanding Officer, Colonel Mahaveer Singh, assigned me a task that would test not just my technical knowledge but my ability to lead and instill confidence. I was to conduct Grenade Throwing practice for twenty soldiers – mostly raw recruits. My assistants were two Havildars – M Sreedharan & NT Mathew – and I was allotted 60 High Explosive (HE) Grenade No. 36.

I looked at the young men assembled before me. Their faces betrayed a quiet fear. The fear of the unknown. The grenade, in regimental lore, had acquired monstrous proportions. Myths swirled around it – tales of unpredictability, of destruction that could turn upon the thrower. My first battle was not against any hypothetical enemy; it was against that fear. My own emotions when I first handled a live grenade back in the academy flooded my consciousness and I was acutely aware that at the end of the day if that fear still lingered in the minds of my boys, I would have failed in my task.

The Weapon: A Legacy of William Mills

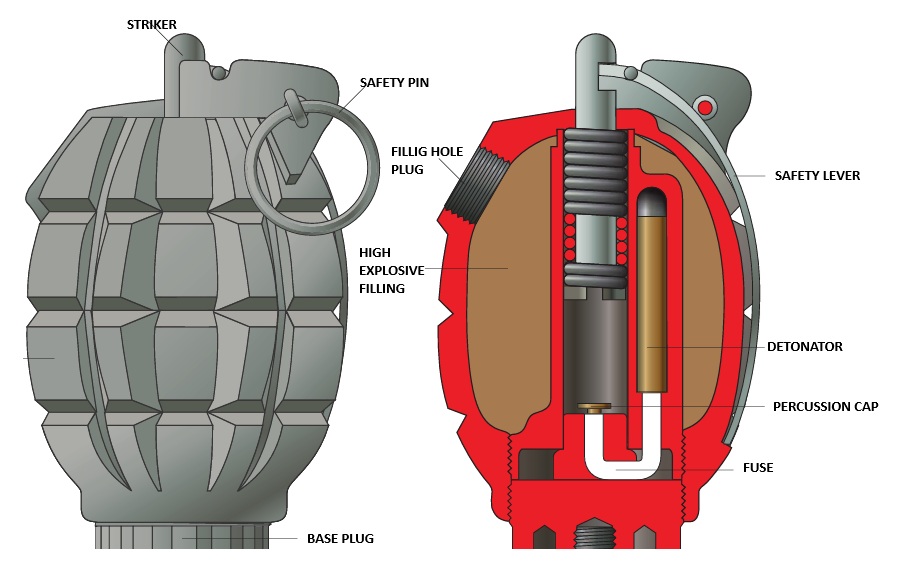

The grenade we were to handle was officially designated the Grenade Hand No. 36M. It was a direct descendant of the Mills Bomb, patented and manufactured by William Mills at the Mills Munition Factory in Birmingham, England, in 1915. Its distinctive pineapple-shaped, cast-iron body was grooved not primarily for fragmentation – contrary to popular belief – but for ease of grip. The waterproof variant, # 36M, had served the British Army through two World Wars.

A bit of theory is always good before practice. And so I began

This was a high-explosive, anti-personnel fragmentation weapon. It could be hand-thrown or rifle-launched. Its central striker was held in place by a close-hand lever, secured by a pin. Upon release, a spring-loaded striker ignited a time-delay fuse. Originally set at seven seconds, combat experience in the Battle of France (1940) proved this delay dangerously generous – defenders could escape or even throw it back. It was reduced to four seconds – and that was the margin between life and death – the 4 seconds that transformed a raw recruit into a seasoned soldier.

Fear Wrapped in a Handful of Serrated Metal

I began with the fundamentals. I explained the mechanism with deliberate calm: hold the lever down, pull the pin with the opposite hand, throw. Release ignites the fuse. Four seconds. Detonation.

Then came the questions. One soldier, earnest and anxious, asked, “Sir, in the movies, they bite the pin off. Is that correct?”

“No,” I said. “You pull it with your fingers. Your teeth are not tools. And remember there is nothing to panic once you pull the pin. It’s perfectly safe so long as the safety lever is in place, firmly held in your hand.”

Another asked, voice barely steady: “Sir, what happens if you drop a primed grenade?”

I looked at the grenade in my hand, lever pressed, pin still in place, I threw it with deliberate force on the desert sand. “Nothing,” I said.

The silence that followed was absolute. In that moment, they understood this was not magic. It was mechanics. It was training. It was trust.

The Practice: Stone to Steel

We began with stones—roughly the size and weight of a grenade. Ideally we should have used drill grenades, but we didn’t have any and so had to make do with stones. They practiced the motion: right arm straight from behind, like an over-arm bowler in cricket. High trajectory. Accuracy over distance. The grenade is a close-quarter weapon; it must clear obstacles and land precisely. A long throw is useless if it misses its mark.

I drilled them on the sequence:

- Grip the grenade in the right hand, base down, lever under the fingers, thumb below the filling screw.

- Left hand through the ring of the safety pin. Face the target. Turn right. Balance.

- Pull the pin downward and backward. Ensure the pin is fully drawn.

- Keep the pin. Return it to the Havildar Mathew for accounting.

- Eyes on the target. Left shoulder pointing. Right knee slightly bent.

- Swing back, bring the arm upright and over. Deliver.

- Observe where it falls. Then take cover.

The Transformation

When the moment came for live throwing, the shadow of fear still lingered on their faces. I asked for volunteers who would throw the first live one. Two hands came up quick fast and then a third very hesitantly. Not bad, I told myself. But I knew instinctively I must do it first. And then the three volunteers. So it was. They threw. They ducked. I pulled them up, made them watch the arc of the grenade, made them see where it fell. Then we ducked together, and the ground shook.

After the first round, something had changed. The visible anxiety had gone. The second round was steadier. The jerky movements changed to a flowing motion. By the third, their faces no longer carried fear—replaced by confidence. They had faced the monster and found it was only metal and mechanics, something that could be mastered by practice and nerve.

What I Learned

That day at Pokhran, I learned that leadership is not about issuing orders. It is about standing beside your men, holding the same weapon, facing the same risk. It is about answering foolish questions without contempt, and dangerous ones without evasion. It is about throwing the grenade first. I also knew that I had earned the unquestioning trust of these twenty boys and many more by word of mouth. I felt immensely happy and allowed myself a small pat. Well done Reji.

Decades later, I remember the weight of that cast-iron body in my palm, the four-second burn, the thud of detonation. But more than that, I remember the faces of twenty young soldiers who learned, in one afternoon, that fear is real but not insurmountable—and that confidence is earned, one throw at a time.

(Images – AI generated)